Click Here to View Our Group Website

Summary of Group Project

Our group decided to cover the thesis, "The Monster's Body is a Cultural Body," which is an excerpt from Cohen's seminal monster piece, The Seven Monster Theses. Our group thesis we covered essentially means that each country influences their monsters in different ways, and because of differences in culture and traditions, variations of monsters arise in different cultures out of initially the same monster. Each member of the group chose a different country, and analyzed how that country's culture influenced the monsters that that culture created.

How My Project Fits into the Group

The country I chose to cover was China, and I quickly got to work researching the various monsters in their culture. Along the way, I found that the vast majority of their monsters were created long ago in Chinese mythology, and that they are ingrained in the daily lives of the Chinese people. My individual thesis expands on our groups thesis: While similarities exist between monsters of different cultures, specific monsters and myths are exclusive to particular societies because the differences in the culture, history, and mythology of each society molds these monsters into reflections of the people's beliefs, fears, and traditions. While I still researched three monsters for my paper, I tried to focus not on specific facts and figures, but on how the culture of China created these monsters. I touched on why many countries have 'purpose monsters', or monsters that are created in order to fulfill a duty in society. My example was the Shui Guo, a creature that lurks in the deep lakes in and around China. This creature drags anybody that strays too far into the water down into the depths of the lake, sometimes resulting in drowning. This monster was created in order to scare children into not wanting to play in the water. I also compared many of my monsters with monsters of different countries and cultures, and pointed out the surprising number of similarities between them. My actual paper is below.

Transformed By Society

While similarities exist between monsters of different cultures, specific monsters and myths are exclusive to particular societies because the differences in the culture, history, and mythology of each society molds these monsters into reflections of the people’s beliefs, fears, and traditions. Despite the close connections that China shares with other Asian countries, its traditions and mythology differ greatly from countries like Japan, Korea, and Russia, which leads to wide-ranging differences in the types of monsters that have been created and passed down from generation to generation. One thing that makes China unique among other Asian countries is its long national history and the relative slowness with which it has adopted modern technology, economics, and social change. The Chinese are heavily influenced by history and traditions rather than recent cultural change and alterations, and their monsters reflect deep-rooted tradition and ancient folklore. One way we can see this is by realizing that the majority of Chinese monsters come directly from centuries-old Chinese mythology, rather than from societal events or political changes.

Cohen, in his seminal analysis of the cultural characteristics of monsters, Monster Culture (Seven Theses), addresses this directly with one of his seven theses: The Monster’s Body is a Cultural Body. Essentially, this means that a particular monster only makes sense when it reflects happenings in a particular culture and era, embodying the real struggles and terrors of a culture while appearing in a fictionalized or fantasy persona that, for the Chinese, is nonetheless frightening. The monster exists to symbolize genuine fears and cannot be seen as a threat if what it reflects isn’t relevant or known to its audience. For example, a monster that was genetically mutated by nuclear testing would only be relevant, if even possible, after 1945, when nuclear energy was actually produced and people understood what radiation was capable of doing. Additionally, Cohen points out that his thesis means that monsters are changed and adapted by a particular culture over time, until that variation of the monster is strictly the property of that particular culture. Monsters are created to play into the fears of a particular society, and that is why they vary so greatly between cultures. A superstitious man in China may fear a Ying Shi because of its vengeful implications in Chinese culture, whereas a man from Finland would only fear a Ying Shi on a purely visual level because the monster has no significance to him or his culture.

In this modern era, however, some monsters are familiar to people in many different countries, due to the popularity and influence of movies and other forms of media. Because of technology such as the internet, it is not only the country that produces this media – for example, monster movies, scary stories, occult comic books – that learns from and adopts their creation, but the global market as well. As technology expands, its not the country of the monster’s or myth’s origin anymore that determines who it belongs to, but the culture that has the most direct hand in its proliferation. American culture, through movies and the internet, has inundated every country in the world in such a way that Americanized monsters, such as Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Werewolf, have become pertinent in modern Chinese culture, appearing to be a form of Americana even though each was born in old European literature.

Because of vast geographical distances that separated them, contact between ancient cultures wasn’t just impractical, it was virtually impossible. Prior to technology and mass media, particular myths and monsters remained the possession of specific cultures or peoples, isolated from contact with others. Surprisingly, though, as we more closely analyze monsters within and between different cultures, we can start to see astounding similarities between the characteristics of monsters indifferent societies, despite their having been created hundreds of years ago with little or no outside contact or influence to shape their legacy. For example, many countries have an undead creature in their monster repertoire, whether it is Frankenstein’s monster in our Euro-American culture, the Bunyip of the Australian Aborigines, or the Ying Shi in Chinese culture. The Bunyip, for example, is a demonic animal that rises out of the water to terrorize innocent swimmers, while the Ying Shi is a human raised from the dead to wreak vengeance on those who it has wronged or who wronged it. And Frankenstein is a blend of both, in that he was human in appearance and psyche, but wholly man-made, which caused fear to the innocent, God-made community around him. In each case, however, the potential victims of the monster are seen as innocent, just, and virtuous, while the monster is the ultimate outsider, unwelcome and totally different. Very few monsters are completely unique to a particular area and culture; rather, they exist as variations of one another, changed by each society in a different way as cultural fears, discoveries, and beliefs evolve.

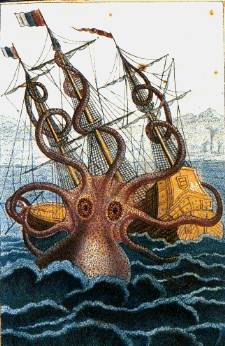

In addition to their shared attributes and physical features, many monsters were created by society to accomplish some purpose. An example of these “purpose monsters” would be the sea monsters feared by sailors of all ethnicities in the 16th to 17th century. While there was no conclusive evidence that, for example, a giant squid ever actually attacked a ship during its voyage across the Atlantic, these terrifying superstitions were created by sailors as a means of warning against the dangers of an across-sea voyage. These sea monster stories were then blown out of proportion as ocean-going merchants and explorers reported even greater hazards than previously imagined, creating the legends that caused great fear amongst sailors for hundreds of years. Now, this example is on the extreme end of the spectrum and had greater influence on economics and exploration than most “purpose monsters.” Another more modern example of a monster created for a specific purpose would be the Chinese tale of the Shui Guo, roughly translated as the “Water Monkey.” This water-dwelling terror is employed not to move entire economies, but to enforce safety and discipline in the family. The Shui Guo is one of the few Chinese monsters that has no roots in mythology; rather, the idea was borrowed from a traditional Japanese monster, the water-dwelling Kappa. Like the Kappa, the Shui Guo is a creature that lurks in deep rivers and lakes, waiting for unsuspecting people to venture too far from the shore. As soon as this happens, the Shui Guo strikes, dragging the person down into the depths of the lake or river, which often results in drowning. In modern Chinese culture, the story of the Shui Guo is used largely by parents to scare young children into keeping out of deep water (Birrell, Chinese Myths).

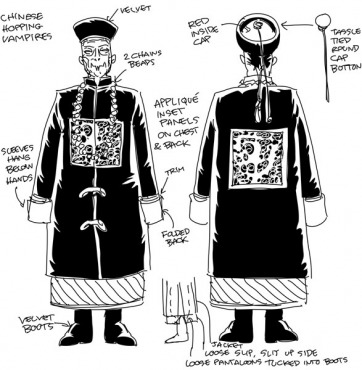

I discussed earlier how many countries have different variations of the same monster-type. An example of this is the vampire. In Chinese culture, this variation is the Ying Shi, literally “stiff corpse,” a mythical undead creature that hops around the countryside for unsuspecting victims. As with most monsters and myths, the origins of the Ying Shi are rooted in attempts to figure out real-life occurrences. The legend of the Ying Shi was likely derived from the ancient Chinese practice of 千里行屍, roughly translated as “Transporting a Corpse over a Thousand Li,” (Encounters of the Spooky Kind). The Li, a Chinese measurement of distance, is roughly equivalent to 1,500 feet. Essentially, this practice implies that when a Chinese person dies away from their homeland, their corpse is transported from the site of death to their home, despite the long distances that often separate the two. For the extensive journey back home, the corpse was placed on long, flexible bamboo rods and carried the vast distances by hand. When traversing the narrow pathways and uneven terrain, the corpses on the bamboo rods often bounced up and down as the pliable bamboo flexed. This is likely how hopping was first attributed to the Ying Shi. Because people often lived hundreds, if not thousands of miles away from their homes due to scattered job opportunities, this practice of having someone escort the corpse home became very popular among the people of China. Actual history aside, the myth of the Ying Shi was most likely established by smugglers in a vain attempt to scare local law enforcement into steering clear of their illicit activities. Smugglers would often conceal their illegal goods in the clothes and possessions of traveling corpses, which predictably made them a direct target for local police forces.

At this point, history and myth begin to diverge and the legend of the Ying Shi begins to take shape. Instead of simply being carried across the countryside to their homeland, legend has it that a Taoist monk would teach the corpse, using magic, to jump on its heels back to its home city. The reason that Ying Shi hop instead of simply walking is strictly because they are struck with rigor mortis, making bending their joints an impossibility. Not all corpses become Ying Shi upon death; there is a set list of circumstances that elicit the transformation from corpse to Ying Shi. Primarily, the person must have murdered someone, committed suicide, or died without fulfilling a just vendetta against a living person. Additionally, a corpse may become a Ying Shi if they caused significant trouble to others in life, e.g. engaged in theft or vandalism, or if their burial service was improperly carried out and thus disrespectful to the ancestors (Newman, 175). The transformation from corpse to Ying Shi is a slow one. They perfectly resemble corpses at first, with their appearance changing based on how long they have been dead. For instance, if the person just died, their Ying Shi corpse will simply be very pale, but as time progresses, the body becomes more and more decayed. Despite death, white hair continues to grow on their heads, regardless of their age at time of death (de Groot, 152). Even Ying Shi children will sport this hair type. After a while, the corpse becomes utterly revolting, often covered by hideous greenish-white mold, rotting flesh, and an emitting an unspeakably foul-smelling odor.

In order to stop these undead creatures, a series of precautions and safeguards were practiced by superstitious and religious citizens alike. According to legend, there was only one way to protect a household from Ying Shi: A six-inch wooden panel, called a threshold, was to be installed on the bottom of each doorway that had outside access (Hopping Mad…). This was done because rigor mortis-stricken Ying Shi are very weak jumpers and cannot hop over this relatively low height. In fact, this tradition became very widespread in the Taoist religion, and to this day, many Taoist temples in the south eastern part of China have a threshold installed in all their doorways.

Physical appearances aside, Ying Shi share some similarities with our popular European vampire archetype. For instance, much like the vampires in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Ying Shi absorb the life essence out of living creatures in order to fulfill their lust for life energy. However, there are distinct and important differences between these vampire variations. For one, the Chinese believe that the mere touch of a Ying Shi is immediately lethal, although, upon death, the human does not become a Ying Shi unless they fulfill the aforementioned special circumstances. In addition, Ying Shi expressly do not drink blood. In fact, the Chinese word for “Dracula”, 衁啜僵屍, is translated as “Blood-sucking Ying Shi,” further demonstrating the differences between blood-sucking vampires and Ying Shi.

In the early 1980’s, Ying Shi were given a new, modern look in society by the suddenly booming Hong Kong movie industry. Through the medium of film, the image and perceptions of the Ying Shi were changed for generations of Chinese movie goers. Characteristics, legends, traditions, and folklore of Ying Shi were all simply created by the directors of this time, with most of them having little to do with the original myth. With the increasing prevalence of Ying Shi in movies, actual Ying Shi history seemed to be overwritten, replaced by a new and improved version that would satisfy the younger generation’s hunger for action and violence.

By adding their own spin to Ying Shi, the directors of these movies did manage to play into the hate that many Chinese citizens, young and old, felt towards a certain historical era, the Qing dynasty. Despite largely creating their own history of Ying Shi, the director’s references to a real historical era gives their movies significance to all Chinese people. To this day, the Qing dynasty is remembered as a time of great sorrow by the majority of native Chinese people, as it was an era where an invading civilization installed a harsh regime that had little regard for the native people. The directors played into this stereotype by dressing the Ying Shi of their movies in traditional Qing dynasty clothing (Hopping Mad…). It is understood that the reason for dressing the Ying Shi in these clothes was to draw a parallel between the vengeful undead creatures and the vicious leaders of the Qing dynasty regime. A Qing era-clothed Ying Shi was not only fearsome, but loathed as a symbol of relentless oppression.

While we as Americans have many names for the demonic forces whose tales are prevalent in our culture, whether ghosts, demons, ghouls, or spirits, the Chinese only have one: the Mo Gui. In Chinese culture, Mo Gui have come to represent anything evil or demonic, and therefore have no definite form. Mo Gui often take the shape of ghosts, ghouls, demons, or invisible evil spirits, anything that represents evil embodied. Although the perceived presence of actual demons has, for the most part, substantially decreased in American culture, they still play a predominant role in the lives of citizens in other countries. Many Chinese traditions, for instance, are largely steeped in the belief and fear of demons and the evil spirits they carry with them. While there are separate names for each kind of entity embodied -- ghost = Gui Hun, evil spirit = Sui, devil = Mo, demon = Yao Mo, etc. -- the Chinese encompass all forms of evil creatures under one umbrella term, the Mo Gui (Werner, A Dictionary…). They tend to reproduce at the first onset of rainfall in the rainy season, because this symbolizes a time of great prosperity and upcoming success (Zhao, 231-246).

Deconstructing the word provides ample evidence as to its deep meaning. The first part, Mo, has its roots in northern India and literally means “evil beings.” It is derived from the Sanskrit word “Mara”, which, according to Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary, means “The principal or ruling evil spirit.” Additionally, the Persian word “Magi” is formed from “Mara,” and that is where we get the English term “magic,” (Gernet, 25). In Buddhist mythology, Mara is the demon of temptation, the source of the evil in the entire world, whose sole purpose in life is to lead people astray and into a life of sin. More proof exists in the Chinese translation of the Hebrew Old Testament bible, where “Satan” is translated into “Mogui.”

While the term Mo is explicitly evil, the term Gui does not necessarily share the same connotation. By definition, Gui simply means “spirit,” though it has taken on a negative connotation in modern Chinese society through its inclusion in the word Mo Gui and related use elsewhere. When used alone, the term Gui has come to refer to the spirits of the deceased, both virtuous and evil, who roam the countryside in search of people who have wronged them. Upon discovery of the offending human, Gui usually inflict bodily harm on the particular individual, with severity of the damage ranging from simple broken bones to death. The degree of injury is largely determined by the degree of damage done by the living person to the recently deceased. Many superstitious families in China take provisions not to offend people who are close to death, as their aggrieved spirit may seek revenge in the afterlife. As a precaution, many people burn, shred, or bury sheets of paper, which denotes money, to appease the Gui and distract them from exacting their terrible vengeance on their family.

Although they still reside under the classification of Mo Gui, Yao Mo, literally “demon,” have their own unique attributes that really set them apart from other Mo Gui. Whereas the majority of evil spirits in Chinese culture were once humans, the term Yao Mo usually refers to the select subgroup of spirits that were formerly animals. Among certain cultures, the term has come to include spiteful fallen angels. In some rare, inexplicable instances, however, humans can become Yao Mo, shedding their human-like traits in replacement for animal-like characteristics. Additionally, Yao Mo differ from other Mo Gui in that most, but not all, of them are evil; some are simply mischievous tricksters. The inherently evil ones are occasionally referred to as Guai Wu, literally “monstrous freak.” According to Journey to the West, the main objective of all Yao Mo is to gain immortality, a feat achieved by capturing and eating a holy man – usually a Taoist monk.

In conclusion, the majority of Chinese monsters were shaped by China’s mythology and traditions and reflect the struggles and fears of the Chinese people. Although they share many parallels with monsters of other cultures, Chinese monsters have in common the truth of Cohen’s thesis: The monster’s body is a cultural body, and points out an important societal reality. A creature, no matter how frightening and horrible, is nothing more than a caricature if it doesn’t embody the fears, challenges, and traditions of the culture it appears in. The monster is what it is because the terrors of the people are manifested in it.