V: Terrorist or Liberator?

While categorically matching the profile of a terrorist, the main character of the graphic novel V for Vendetta, through various acts of terrorism against an oppressive regime, causes the reader to rethink the stereotypical “evil” designation instantly given to terrorists like V as well as the concept of terrorism itself. Throughout the book, the reader feels a full spectrum of emotions toward the protagonist, varying from searing disgust to sadistic delight in his actions. Ranging from assassinations of key political figures to detonating explosives on important landmarks, the actions of V lead the reader to draw their own conclusions about whether he is ‘good,’ ‘evil,’ or some combination of the two. In addition to causing readers to judge V by his actions, this graphic novel makes one think whether or not acts of terrorism can be excused, and, further, whether the killing of innocent people can ever be justified in the name of freedom and liberty.

From the very first scene of the book, the mysterious character V reveals himself to be a protector of the weak, regardless of the potential harsh consequences. Reading further into the book, we begin to make out a progressively clearer representation of V’s ideals. Events such as his scathing one-way argument with the statue of Madam Justice show us what he thinks of the present regime and sheds insight into many of his thoughts on politics, freedom, justice, and liberty.

Though there are many important events that help develop the story in V for Vendetta, V’s one-way discussion with Madam Justice perhaps explains most clearly V’s disgust with the level of injustice he sees around him, and what he plans to do about it. Madam Justice, though somewhat eerily and ironically resembling our own Statue of Liberty, appears to watch over the city of London, extending a promise of justice and liberty to all of its citizens. However, V makes it clear through his monologue that her promise is as hollow as the now-empty chambers of the parliament building. Cursing this false representation of justice, V decries, through a series of faux conversations with the statue, her broken promise of liberty to her citizens. No longer does she symbolize the freedom that she once exemplified; instead she has become an immovable figurehead representing the harsh reality of governmental oppression. Once, her gaze rested on the free peoples of London, commanding a level of respect from young and old; now, she balefully stares at the exploited population, offering them only empty assurances and the memory of a better era. During the monologue, V frequently mentions how she has whored herself out to the highest bidder, instead of standing true to her roots and ideals. Using a metaphor of anarchy as a sweeter mistress than Madam Justice, he makes a very important statement that illustrates his entire philosophy throughout the book, that being that a government run by corrupt individuals is no better, and in this case is worse, than anarchy. The idea of anarchy is something V embraces as his eyes are opened to the reality of the hopelessness that corruption has wrought around him. After acknowledging the admiration for Madam Justice he had when he was a child, V can’t bear the sight of her anymore, and in defiance detonates a bomb at her feet. I think this is one of the pivotal points in the graphic novel because if, for nothing else, it is this violent act that V offers as an explanation of the motives behind his string of bombings. Additionally it gives subtle hints as to who V is as a person, both through descriptions of the impact Madam Justice had on him as a child as well as through the way he talks of her empty promises of liberty and freedom that lull his countrymen into complacency. I think that this scene is arguably the most important scene in the book because it vividly demonstrates V’s beliefs and goals, setting him apart from the passivity of his fellow citizens and at the same time coloring him as more than just a violent radical.

An important turning point in the book is when Dr. Delia Surridge’s journal is found, because it reveals important plot details about V’s history, what motivates his seemingly random vendetta against government officials, and how he grew to become superior in physical power, intelligence, and ability to any other human. These three things are pivotal for the understanding of the book because they show the reader that V isn’t just another rebellious human. He instead is a chemically engineered byproduct of the Larkhill resettlement camps, armed with the sole mission of killing anybody who contributed to the torture and murder of thousands of innocent people at the camp. While the motives for V’s assassinations of the former workers seem fairly obvious -- to avenge the torture and years of agony endured by him and others -- there are additional hidden motives for his killing spree. First, in order to keep his identity a secret, he must kill anybody who could possibly know who he is. Since he is the sole survivor of the chemically mutated prisoners, the only people that could know his identity are the people who worked at the camp; from this, his hit list is born. Second, he uses these attacks and assassinations to distract the government’s resources from the very thing they should be focusing on: V’s inherent goal of bringing down their fascist government and establishing anarchy where voluntary order and control can occur.

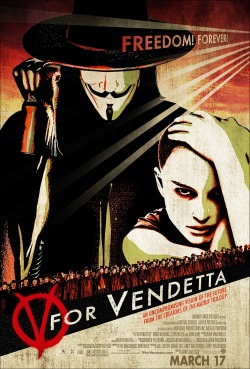

Title.

Another important turning point is the surreal scene where V tricks Evey into thinking she is imprisoned in a jail cell after the attempted murder of Alastair Harper. Her belongings taken and her hair shaved, she is forced to endure a level of suffering that vividly emulates what V went through at Larkhill. After torturing her in this rhetorical prison, her interrogator finally offers her a choice: to give in and admit that she collaborated with V in his murderous rampage, or to die alone, forgotten by humanity. Feeding off strength that Valerie’s letter has bestowed on her, Evey selflessly pronounces that she’d rather die than betray her friend V, unequivocally matching Valerie’s noble deed. Having passed the test, she is told by her interrogator that she can go. Running down the empty hallway of the correctional facility, she opens the door to find herself once again in the Shadow Gallery. At first, she is justifiably furious that V would trick and torture her so vividly in order to make a point, but her anger subsides when, on the roof of the Shadow Gallery, she is able to accept her newfound freedom for what it is: an unquestionably essential element required for one to truly live. This scene is important because it shows the necessity of the test, which opened Evey’s eyes to the horrors of the oppressed world that she lives in, giving her a glimpse of a level and depth of freedom that she had once never known existed. Without passing this crucial test, Evey could never have truly replaced V because her views on justice were still skewed by the society in which she lives. Freedom to V, and later to Evey, means a life without persecution and involuntary rule; a life where citizens are free to make their own decisions and pick their own leaders.

This book sheds light on many of the same ethical and moral dilemmas that we as humans face in our day-to-day lives. For example, economist and philosopher John Locke, through his Social Contract Theory, explains that often people will put up with a cruel regime for an indefinite period of time, despite the overwhelming oppression and tyranny, until a particular event sparks an all-out rebellion. We witness this tyranny in V for Vendetta and are able to see how V is trying to spark that rebellion by his own acts of terrorism. Only after his death and Evey’s assumption of his duties does the insurrection that he so strongly desired finally take place, plunging England into the anarchy he gave his life for. In addition to modeling John Locke’s theory, V for Vendetta demonstrates the concept of institutional evil almost to perfection. It’s easy to think of everyone who worked for the government in the book as evil. However, much like how the majority of people in Nazi Germany didn’t share the same radical beliefs that their fascist leaders did, they nonetheless turned a blind eye to the destruction, and, through apathy, allowing their core beliefs to take a backseat to the willpower of others. Reflecting on this point, one has to think to oneself about which characters in the book are actually evil. At first glance, anybody who is against V seems to be inherently bad, but after looking through the characters again, a startling few fit my description of ‘evil’; most just seem to be doing their jobs.

While offering quite a few ideas and concepts to think about, possibly the most controversial theme V for Vendetta touches on is the idea of whether or not freedom and liberty are so valuable to a society that almost any wrong is acceptable as long as freedom prevails in the end. Lacking a working cost-benefit analysis, this reasoning is ethically flawed according to the theory of consequentialism. For example, undoubtedly many innocent people die in the terrorist acts carried out by V, and what benefit do they bring? Nothing, at first. However, we see in the case of V for Vendetta that the benefit eventually outweighs the cost, because the government is brought to its knees by the end of the book, giving citizens the freedom and liberty that they didn’t know they could ever achieve. In this particular case, V’s actions are justified, in my opinion. However, if he failed in his plot and simply died without overthrowing the government, his actions would be sharply looked down upon as murderous acts of terrorism. Through the medium of a graphic novel, writers Alan Moore and David Lloyd are able to illustrate the smothering oppression more vividly than can be expressed by mere words alone; the brooding, dark qualities of the pen-and-ink drawings cast a feeling of darkness throughout the storyline.